Travelling North

Sydney Theatre Company and Allens present TRAVELLING NORTH by David Williamson at Wharf 1, Hickson Road, Walsh Bay.

David Wiiliamson’s TRAVELLING NORTH was first performed at the Nimrod Theatre, Sydney, in August, 1979, directed by John Bell. This play was the ninth in an output that had established David Williamson as the most prolific and ‘bankable’ writer that the Australian theatre had ever produced: THE REMOVALISTS (1971), DON’S PARTY(1971), THE DEPARTMENT (1975), THE CLUB (1977), amongst others, were proof of that last claim. To produce a David Willliamson play was to virtually ensure a good box office return – money in the bank for that lucky theatre company – for Mr Williamson had his fingers, exactly, on the pulse of the Australian psyche and foibles, and his audience relished it with great and grateful appetite. Mostly, they still do.

What marked TRAVELLING NORTH as different in his out put up to that time was the unique characterisation and plotting of a kind of romantic ‘memory’ play. It was, in my estimation, his first play that gave us characters that were not just recognisable ‘agents’ for his socially satiric critique of the Australian scene, but, also, deeply observed emotional characters with a tender mixture of human frailties and failures dealing with the big realities of life, specifically, ageing and death. Frankly, a love story, leavened with crisp, comic sentiment and not a scintilla of sentimentality. It was, as well, the first play of his to have satisfying, sympathetic observations of the female of the Australian species. There was with Frances, but too, with the daughters, Helen (Harriet Dyer), Sophie (Sara West) and Joan (Emily Russell), an insight of empathetic comprehension to the cause and effect of the origin of the behaviour of these women – they were not just slender caricatures positioned to be the butt of sexist jokes, as in other of his earlier plays. These women were understood and respected.

Frank (Bryan Brown), a war veteran in his 70’s, a retired engineer, socialist, has found a companion, Frances (Alison Whyte), in her middle 50’s, who is willing to travel north with him, from Melbourne, to find and live out the dreams of the ‘mythic’ promise that the tropics have always proffered to the Australian psyche. Says Frank to Frances: “We’re going to lead the ideal life. We’ll read, fish, laze, love and lay in the sun. … it’s time you started enjoying life. … You’re my companion not my slave, and that’s the way it’s going to stay.” Not since THE SUMMER OF THE SEVENTEENTH DOLL had the ‘North’ had such an alluring promise of a place of magic. Unfortunately, for them both, nature makes its call, and takes a toll on those dreams.

Frances stands alone on stage at the beginning of the play looking and listening, contemplating, perhaps a dream, in the warm, tropical atmosphere of a late Queensland afternoon, to be startled, that Mr Williamson indicates, comes from “an underlying tension and anxiety”, by the entrance of Frank.The play finishes with Frances with a champagne glass in her hand, outdoors in the garden, to the swelling music of Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto number three, declaring, though now alone, claiming, her freedom to “go travelling further north.” Having, through the course of the play, been tested by the demands of her unhappy daughters, and the perturbations of the dying and demanding Frank, Frances has at last reached a state of real release that will permit her to really begin her own quest for independence and self-realisation. TRAVELLING NORTH, is, indeed, the journey of the burgeoning ‘modern’ Australian woman, unharnessing herself from the subjugations of family, and duty to men, and be an actualised ‘self’. The play is set in a time of great cultural and social changes in Australia – the period between 1969 and 1972 – and the given circumstances of the “when” of this play, is a significant metaphor of the promised optimism for all of it’s ‘peoples’, for change.

This production of TRAVELLING NORTH, Directed by Andrew Upton (only his sixth production as director at the STC – it has been interesting to watch his development) is set on a shining, gleaming wooden set of platforms of rising steps, (I could not help but see visual connection to the configuration of the pink granite steps and platforms to the outside entrances at the Sydney Opera House, and remember its connections to the sacrificial steps of its Inca inspiration), sitting in a stripped back theatre wall-‘box’. It is a formidably bare and challenging image – it is a follow-up by the Designer, David Fleischer to his and Director, Andrew Upton’s ‘installation art’ piece, that they created for their production of Joanna Murray-Smith’s FURY, in this theatre, last year. That design, did not facilitate the flow or imagery of that play and neither does this design contribute much to this play (the irony of steps to be negotiated by older characters in the play, did not pass by my knees and hip objections without my consciousness ringing alarm bells). The set design’s visual aridity is compensated, mostly, with lighting atmospherics for the two climatic extremes of Queensland and Melbourne by Nick Schlieper. This production has no furniture, except for a recliner chair, carried, late in the play, to the highest platform by the dying Frank, and acts, it seemed to me, as a kind of metaphorical throne, for the forced directorial imagery of a ‘King Lear’ inheritance for Frank, struggling with the “Goneril and Regan’s”, that he names the children of Frances, by this team of artists. There are, as well, next to no properties. The costuming, also, by Mr Fleischer, are fairly accurate creations that would be seen, just as legitimately on mannequins in a museum exhibition at the Powerhouse Museum – the wigs and make-ups are all over-stylised exaggerations, reminiscent of the work of Diana Vreeland in her costume exhibition work, recently featured in the wonderful documentary of her career. They hardly appear to be clothes or accoutrements worn by ordinary people.

This ‘post-modernist’ stripping to essences in the set design and presentation of couture exaggerations in costume and period look, does not assist this play, that seems to cry out for a naturalism to nurture the ‘melodrama’ of the play’s pre-occupations. In taking such licence with the visual world of the play, Mr Upton, certainly, then, is making demands on his actors to create so much more, imaginatively, than the experiencing of the circumstances of the emotional narrative. These actors must create the entire world of the play (setting and practical details), and so have to speak not only with their voices, but, also, with their eyes, so that we, too, can see the whole world of the play that they exist in, and interpret Mr Williamson’s intentions. The capability of all is variant- some can, some can’t or don’t.

The casting of this production and the performances that we are given, directed by Mr Upton, seem to lack emotional intelligence. Like the design, the acting from most of the actors has been reduced to the simple pragmatic essences of the action of the characters, without any deep or true motivational study, to a kind of imaginative aridity of expression. Mr Williamson’s plays work best when the actors bring the ‘homework’ of the Stanislavskian realities of acting technique to their characters. Russell Kiefel, as the Doctor, Saul; Andrew Tighe, as Freddy and Emily Russell, as Joan, do best, and create, within the limitations of the direction, some real glimmers of the humanity that this text cries out for.

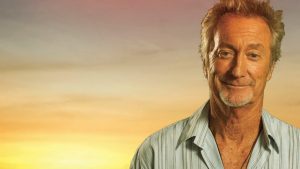

Bryan Brown, who is a film actor of some breadth of experience, and looks every physical inch a desirable catch for any woman – still has the matinee idol potentcy, physical glamour, even in shorts – has had a very limited history of theatre performance (most of it with the STC, in production of THE RAIN DANCERS and ZEBRA, two productions spread over some 15 or so years), and seems to be out of his comfort zone here, labouring under the strain of the verbal accuracy and responsibility of the role on the stage. He gives the appearance of a tentative line reciter and hardly deviates in character development from a narrowly conceived journey – that is, from irascibility to death, with some studied and grafted externalisations of physical decline – and rarely seems to be listening to the other actors in his scenes to any palpable effect or change. There is a kind of ‘deer-caught-in-the-headlights’ demeanour visible, which is distracting from the type of masculine bully, that Mr Williamson has written. True, there is a memory of the late Frank Wilson’s original creation, and the film performance of Leo McKern, lingering, to persuade me that Mr Brown’s performance lacks emotional depth or the ability to express it on the stage, which could be declared unfair, on my part. But Mr Brown’s performance does lack the open and free emotional dynamics, that we may have witnessed in his film and television work.

Ms Dyer as the emotionally injured Helen, one of Frances’ daughters, simply plays the superficial actions of her character and that she does not reveal the comedy or warmth as part of her perception of Mr Williamson’s writing, is astonishing. Ms Dyer recently won the Best Actress Award from the Sydney Critics for her work in MACHINAL, and that those qualities are not on show here, is an alarming disappointment – is it the difference in direction that makes this work so pallid? Ms West, as the other more sympathetic daughter, Sophie, seems, mostly, out of her depth in any appearance of complicated empathy or insight to the character’s difficult position and journey in the course of the play. Again, I found it curious, that while watching this production, the original performances of Jennifer Hagan and Julie Hamilton, from some 35 years ago, came roaring back to me, vividly, as deeply funny and deeply affecting revelations of complicated women. Perhaps, Ms Dyer and West and Mr Upton have no reference points for such women of that time and play over the surfaces of the text.

Alison Whyte is now playing Frances as a consequence to the indisposition of Greta Scacchi – maybe all those stairs in the design were prohibitive – and has had little time to develop the character to much depth. Ms Whyte seems to be cooly cocooned in the concentration of ‘learning’ the play and the complex opportunities of this role evade her as yet, which, of course, does not serve Mr Williamson’s intentions well. It is a cold figure that we watch, and the necessary chemistry between Frances and Frank, as well with the other characters, is mostly absent. One wonders what Ms Scacchi might have brought to this leading role in the play. Ms Scaccchi, like Mr Brown, is a film actor of some note, but also, has had a very wide and famous experience in the theatre. Certainly, her warmth and emotional intelligence would have made her ideal casting for this very significant Australian character, and may have brought some redress to the balancing of the dramaturgy in the scheme of the writing intentions in this misconceived production.

Philip Parsons in his introductory essay to the Currency Press publication of the text of TRAVELLING NORTH (1980), is laudatory of its virtuosic writing. Constructed almost cinematically over some thirty three scenes, the intricacies of the subtle contrasts and juxtapositioning of the order of the scenes with a masterly conception and execution of development of plot, character and theme, is beautifully expurgated and worth reading. To be able to distinguish between the qualities of a good play and a good production is the concern of the discerning and regular theatre goer.

This production of this good play is inadequate in revealing why it is one of the cherished plays in the Australian repertoire. We shall have to wait a while longer to another production, to appreciate the joys of the playwriting of David Williamson in this wonderfully human work.

Sad to tell you, dear diary. Sad to say.

One reply to “Travelling North”

I remember a wonderful production of this play in 1980 at the Theatre Royal in Sydney. Frank Wilson, Carol Raye, Jennifer Hagan, Julie Hamilton. Directed by John Bell.

I saw it many times as I was working as an usher at the theatre. Enjoyed it each time, particularly Jennifer Hagan as the neurotic daughter.

Comments are closed.